Jacked was something I wanted to put together for a long time. It’s funny because just as in the industry, stories and ideas formulate early on and can take up to a year to shoot – most, even longer. Brandon Meyer spit an interesting idea at me while shooting Rough Draught. His pitch was simple and hilarious. “Three burglars try to steal a car – at the same time.” Loved it. It took about a year until I was able to find time to do it. I had moved to LA from Florida, and luckily, so did a handful of kids from my film school class. I didn’t have to network much to obtain hands to handle the production. But I needed a script first. I had a meeting with Jeremy Fox to discuss the script. I gave Jeremy free roam to create the characters to his fancy, and only suggested that the banter between them be clever. In approximately 48 hours, this nice guy sent me a complete script.

I researched the process of shooting inside a car. What are the challenges? What are the complications? How can I keep this thing organized? I decided it would be best to storyboard. I briefly hired a storyboard artist, someone with very little experience in creating storyboards, yet my lack of good direction nearly scared her away. I needed to do this myself. Early on in my career, I had a knack for outsourcing almost everything I could in order to focus on directing (or editing, or whatever major creative role I was playing in a project). In Jacked, I was having so much trouble describing what I wanted that it only seemed best to create my own storyboards. I’m in no way an artist, and I met with Kyle Hardesty to show him what I had drawn.

Kyle: “So, we’re shooting in an airplane? Why does the pilot have a mohawk?”

During this time, I was also casting for the film. A good friend from school recommended Nathan Danforth, and Nathan suggested Andrew Roach to play opposite him. The two were working as valet guys at the Chateau Marmont in Hollywood at the time, and said we’d be clear to shoot in its underground parking garage.

We weren’t one take in before security came and busted us. This was the first moment where I felt I truly failed. Where I felt this project was impossible. The cast and crew patted me on the back and suggested we head to Sardo’s in Burbank to get sloshed. It’s one thing to get shutdown on a gig with a budget, but when people are working for free and selling favors, it’s a heartbreak.

I had to do this. The script was easy – one location, five actors, two cameras. How hard could this be? Why did I fall asleep in producing class during the location permit lecture? I could do this. I just need a location…

One of the supporting actors in the film happened to teach 3rd graders at an elementary school in Beverly Hills. He spoke with the principal, and as long as I were to donate a few hundred bucks to the school, I could shoot in the parking garage on a Sunday. That’s one day to shoot. Eight hours. It can be done. Once again, I have time to prepare.

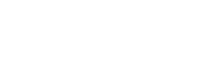

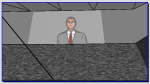

I scoured the internet for a way to create legible storyboard panels. I came across a few programs, but Frame Forge happened to be the right fit for me. It allowed me to create my own shots in 3D space using props, settings, and directions. I was even able to adjust the focal length of the camera, and change the expressions on the faces of the actor props. I’m an avid player of The Sims, so this was quite easy to pick up.

I researched the process of shooting inside a car. What are the challenges? What are the complications? How can I keep this thing organized? I decided it would be best to storyboard. I briefly hired a storyboard artist, someone with very little experience in creating storyboards, yet my lack of good direction nearly scared her away. I needed to do this myself. Early on in my career, I had a knack for outsourcing almost everything I could in order to focus on directing (or editing, or whatever major creative role I was playing in a project). In Jacked, I was having so much trouble describing what I wanted that it only seemed best to create my own storyboards. I’m in no way an artist, and I met with Kyle Hardesty to show him what I had drawn.

Kyle: “So, we’re shooting in an airplane? Why does the pilot have a mohawk?”

During this time, I was also casting for the film. A good friend from school recommended Nathan Danforth, and Nathan suggested Andrew Roach to play opposite him. The two were working as valet guys at the Chateau Marmont in Hollywood at the time, and said we’d be clear to shoot in its underground parking garage.

We weren’t one take in before security came and busted us. This was the first moment where I felt I truly failed. Where I felt this project was impossible. The cast and crew patted me on the back and suggested we head to Sardo’s in Burbank to get sloshed. It’s one thing to get shutdown on a gig with a budget, but when people are working for free and selling favors, it’s a heartbreak.

I had to do this. The script was easy – one location, five actors, two cameras. How hard could this be? Why did I fall asleep in producing class during the location permit lecture? I could do this. I just need a location…

One of the supporting actors in the film happened to teach 3rd graders at an elementary school in Beverly Hills. He spoke with the principal, and as long as I were to donate a few hundred bucks to the school, I could shoot in the parking garage on a Sunday. That’s one day to shoot. Eight hours. It can be done. Once again, I have time to prepare.

I scoured the internet for a way to create legible storyboard panels. I came across a few programs, but Frame Forge happened to be the right fit for me. It allowed me to create my own shots in 3D space using props, settings, and directions. I was even able to adjust the focal length of the camera, and change the expressions on the faces of the actor props. I’m an avid player of The Sims, so this was quite easy to pick up.

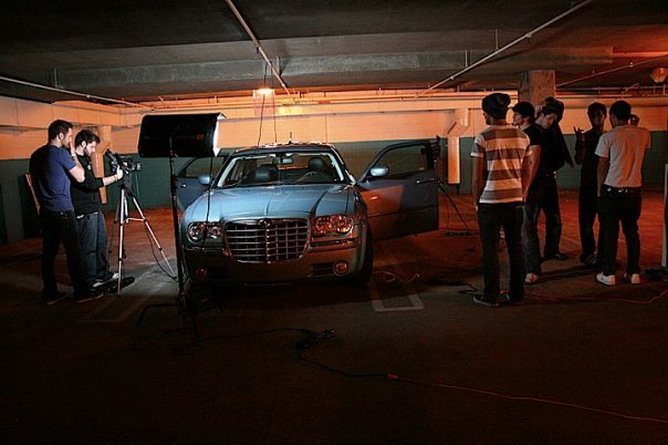

I aligned my storyboards to the shot list, and geared up to shoot. I wanted to specifically use a Chrysler 300 for the car – mainly because it’s classy for a neo-noir genre. I found a guy on Craigslist who let us use his car for $75 for the day. He even washed and detailed it beforehand. Nice guy. I was ready to shoot the first shot ahead of schedule until a problem was discovered – the parking garage ventilation system’s fan motor refused to shut off. Alfredo Marun, my 1st AD at the time, alerted the elementary school’s janitor to fix the problem, yet he couldn’t turn the fan off. We routed lavalier mics and set up a plant mic in the car to cover different grounds to see what sounds better in post. Better safe than sorry…

Audio was the only major problem on set. We set up two cameras, pushed them far back, and zoomed in to get the interiors of the car. Continuity wasn’t broken so much, since it was difficult to tell if the windows were rolled down or not. Overall, the shots were simple to get, thanks to the storyboarding of every shot. My routine was as simple as asking Alfredo what shot was next, and lining it up with the storyboards I held in my hands. This made it simple for the crew to know what to set up, and there was practically never a still moment on set. From setup to breakdown, production was accomplished in less than eight hours and cost less than $500 to produce (2/3 of that went toward the location).

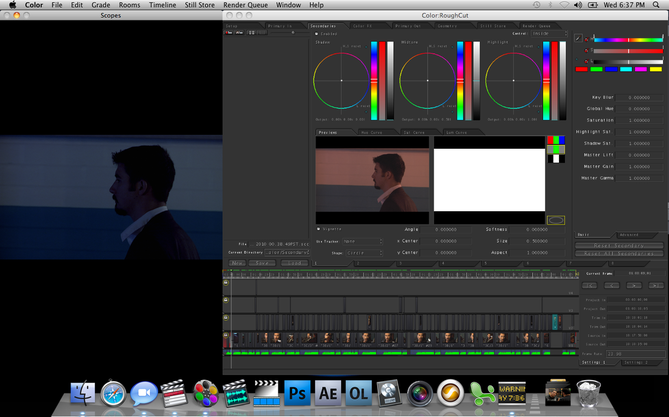

In post, I had a lot to work with. The banter back and forth was fun to assemble and I was able to mix and match different takes from all of the improv that was done. Color was a small task, as I wanted to have a cool blue tint with some grain… the original footage were very pinkish.

I worked with a good audio friend of mine, Mike Carr, to clean up the audio. He was working on Avatar at the time, and was nice enough to work with me for a couple of sessions to get that nasty fan out of the mix. I exported my audio splits into OMF’s and he did his magic.

Ultimately, I consider this project an accomplishment. It was a failed attempt brought back to life with an inspirational group of talent and a remarkable crew. Looking back, it’s a blessing I was shut down for the fact that I wouldn’t have had proper storyboards and extra rehearsal time. You also learn a lot from your previous works; my first film was ridden with tons of problems and casting issues as a result of poor pre-production. When you keep things simple and plan them correctly, you wont have a microwave oven go off during a shot or have only four extras show up to a party scene. The $500 budget for Jacked was also used for minor equipment rentals, extension cables, and lots of Red Vines.

Ultimately, I consider this project an accomplishment. It was a failed attempt brought back to life with an inspirational group of talent and a remarkable crew. Looking back, it’s a blessing I was shut down for the fact that I wouldn’t have had proper storyboards and extra rehearsal time. You also learn a lot from your previous works; my first film was ridden with tons of problems and casting issues as a result of poor pre-production. When you keep things simple and plan them correctly, you wont have a microwave oven go off during a shot or have only four extras show up to a party scene. The $500 budget for Jacked was also used for minor equipment rentals, extension cables, and lots of Red Vines.

Here's the final product:

And here's behind the scenes:

RSS Feed

RSS Feed